Bed Bath and Beyond Art Tpe Trnty 14 X 16

A nazar, an amulet to ward off the evil eye

An amulet, as well known as a practiced luck amuse, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The give-and-take "amulet" comes from the Latin word amuletum, which Pliny'south Natural History describes every bit "an object that protects a person from trouble". Anything can role equally an amulet; items commonly and so used include statues, coins, drawings, plant parts, animate being parts, and written words.[one]

Amulets which are said to derive their extraordinary properties and powers from magic or those which impart luck are typically part of folk religion or paganism, whereas amulets or sacred objects of formalised mainstream organized religion as in Christianity are believed to take no ability of their own without faith in Jesus and existence blessed by a clergyman, and they supposedly will as well not provide any preternatural do good to the bearer who does not have an advisable disposition. Talisman and amulets take interchangeable pregnant. Amulets refer to any object which holds an apotropaic role. An amulet is an object that is by and large worn for protection and fabricated from a durable cloth (metal or hard-stone). Amulets can be applied to paper examples also; however, the word 'talisman' is typically used to describe these.[2] Amulets are sometimes confused with pendants, pocket-sized aesthetic objects that hang from necklaces. Any given pendant may indeed be an amulet but and then may whatever other object that purportedly protects its holder from danger.

Ancient Egypt [edit]

The use of amulets (meket) was widespread among both living and expressionless ancient Egyptians.[iii] [4] : 66 They were used for protection and as a means of "...reaffirming the fundamental fairness of the universe".[5] The oldest amulets found are from the predynastic Badarian Period, and they persisted all the way through to Roman times.[6]

Pregnant women would wear amulets depicting Taweret, the goddess of childbirth, to protect confronting miscarriage.[4] : 44 The god Bes, who had the head of a lion and the trunk of a dwarf, was believed to be the protector of children.[4] : 44 Later on giving birth, a mother would remove her Taweret amulet and put on a new amulet representing Bes.[4] : 44

Amulets depicted specific symbols, amidst the well-nigh mutual are the ankh and the Centre of Horus, which represented the new eye given to Horus past the god Thoth as a replacement for his old middle, which had been destroyed during a boxing with Horus's uncle Seth.[4] : 67 Amulets were often made to represent gods, animals or hieroglyphs.[3] [7] [4] : 67 For instance, the mutual amulet shape the scarab protrude is the emblem of the god Khepri.[3] [4] : 67

The nearly common textile for such amulets was a kind of ceramic known every bit Egyptian faience or tjehenet, simply amulets were also made of stone, metal, bone, wood and gilt.[four] : 66 [7] Phylacteries containing texts were another common class of amulet.[8]

Like the Mesopotamians, the aboriginal Egyptians had no distinction between the categories magic and medicine. Indeed for them "...organized religion was a potent and legitimate tool for affecting magical cures".[9] Each treatment was a complementary combination of applied medicine and magical spells. Magical spells against snakebite are the oldest magical remedies known from Egypt.[10]

The Egyptians believed that diseases stemmed from both supernatural and natural causes [11] The symptoms of the disease adamant which deity the doctor needed to invoke in order to cure it.[11]

Doctors were extremely expensive, therefore, for most everyday purposes, the average Egyptian would have relied on individuals who were not professional doctors, but who possessed some form of medical training or noesis.[11] Among these individuals were folk healers and seers, who could fix broken bones, aid mothers in giving birth, prescribe herbal remedies for common ailments, and interpret dreams. If a md or seer was unavailable, then everyday people would simply cast their spells on their own without assistance. It was probable commonplace for individuals to memorize spells and incantations for later on utilise.[xi]

Ancient Rome [edit]

Amulet, amber, with ear of wheat, Roman period (69-96 AD)

Amulets were particularly prevalent in ancient Roman gild, being the inheritor of the ancient Greek tradition, and inextricably linked to Roman religion and magic (see magic in the Graeco-Roman world). Amulets are usually outside of the normal sphere of religious experience, though associations betwixt certain gemstones and gods has been suggested. For example, Jupiter is represented on milky chalcedony, Sol on heliotrope, Mars on red jasper, Ceres on greenish jasper, and Bacchus on amethyst.[12] Amulets are worn to imbue the wearer with the associated powers of the gods rather than for any reasons of piety. The intrinsic power of the amulet is also evident from others bearing inscriptions, such equally vterfexix (utere fexix) or "good luck to the user."[13] Amulet boxes could likewise be used, such equally the instance from function of the Thetford treasure, Norfolk, UK, where a gold box intended for pause effectually the neck was found to contain sulphur for its apotropaic (evil-repelling) qualities.[14] Children wore bullas and lunulas, and could be protected by amulet-chains known as Crepundia.[xv] [16]

Near Eastern amulets [edit]

Metal amulets in the form of flat sheets fabricated of silver, gold, copper, and lead were also popular in Late Antiquity in Palestine and Syria as well equally their adjacent countries (Mesopotamia, Minor Asia, Iran). Usually they were rolled up and placed in a metallic container with loops[17] to be carried past a necklace. They were incised with a needle with manifold incantation formulars and citations and references to the proper name of God (Tetragrammaton).[xviii] Nearly of them are composed in diverse kinds of Aramaic (Jewish Aramaic, Samaritan Aramaic, Christian Palestinian Aramaic, Mandaic, Syriac) and Hebrew,[nineteen] [twenty] but there be besides sometimes combinations with Greek.[21] [22]

Mainland china, Korea, Japan [edit]

A selection of omamori, Japanese amulets

In China, Taoist experts called fulu developed a special fashion of calligraphy that they said would be able to protect against evil spirits.[23] The equivalent type of amulet in Nippon is chosen an ofuda. Mamorifuda are gofu amulets, In Korea, This is Where Chosen Bujeok (부적) fifty-fifty usually in tradition of Taoist Korean Rituals, that are talismans encased inside in modest brocade bags that are carried on the person.[24]

Abrahamic religions [edit]

In antiquity and the Middle Ages, most Jews, Christians, and Muslims in the Orient believed in the protective and healing power of amulets or blessed objects. Talismans used past these peoples tin be broken downwardly into 3 main categories: talismans carried or worn on the body, talismans hung upon or above the bed of an infirm person, and medicinal talismans. This third category can exist farther divided into external and internal talismans. For instance, an external amulet can be placed in a bath.

Jews, Christians, and Muslims have also at times used their holy books in a talisman-like manner in grave situations. For example, a bed-ridden and seriously ill person would have a holy book placed nether part of the bed or absorber.[25]

Judaism [edit]

Chai pendant (modern)

Examples of Mitt of Miriam in contemporary Israel

Amulets are plentiful in the Jewish tradition, with examples of Solomon-era amulets existing in many museums. Due to the proscription of idols and other graven images in Judaism, Jewish amulets emphasize text and names. The shape, material, and color of a Jewish amulet makes no deviation. Examples of textual amulets include the Silver Scroll, circa 630 BCE, and the withal contemporary mezuzah[26] and tefillin.[27] A counter-example, nevertheless, is the Mitt of Miriam, an outline of a human hand. Some other non-textual amulet is the Seal of Solomon, besides known as the hexagram or Star of David. In i form. it consists of ii intertwined equilateral triangles, and in this form it is commonly worn suspended around the neck to this day.

Another common amulet in contemporary apply is the Chai (symbol)—(Hebrew: חַי "living" ḥay ), which is also worn effectually the neck. Other similar amulets still in utilize consist of ane of the names of the god of Judaism, such equally ה (He), יה (YaH), or שדי (Shaddai), inscribed on a piece of parchment or metallic, usually argent.[28]

Among Jewish children in the 2nd-century CE, the practice of wearing amulets (Hebrew: קמיעין) was so pervasive that one could distinguish betwixt a Jewish kid (who usually donned an amulet) and a non-Jewish kid who did non usually habiliment them.[29] During the Middle Ages, Maimonides and Sherira Gaon (and his son Hai Gaon) opposed the use of amulets and derided the "folly of amulet writers."[30] Other rabbis, however, canonical the apply of amulets.[31]

The wearing of phylacteries has been seen past others as another grade of amulet, worn for protection.[32]

Rabbi and famous kabbalist Naphtali ben Isaac Katz ("Ha-Kohen," 1645–1719) was said to exist an expert in the magical utilize of amulets. He was accused of causing a fire that bankrupt out in his house and then destroyed the whole Jewish quarter of Frankfurt, and of preventing the extinguishing of the fire by conventional ways because he wanted to test the ability of his amulets; he was imprisoned and forced to resign his post and leave the city.[33]

Christianity [edit]

A pendant crucifix, considered in Christian tradition as a defence confronting demons, every bit the holy sign of Christ'due south victory over every evil

In Christianity, regularly attending church, frequently receiving Holy Communion, Bible study, and a consistent prayer life are taught as existence amidst the all-time ways to ward against demonic influence.[34] The Cosmic, Oriental Orthodox, Eastern Orthodox, Lutheran, Anglican and Pentecostal denominations of Christianity hold that the use of sacramentals in its proper disposition is encouraged simply past a firm faith and devotion to the Triune God, and not by any magical or superstitious belief bestowed on the sacramental. In this regard, prayer cloths, holy oil, prayer beads, cords, scapulars, medals, and other devotional religious paraphernalia derive their ability, not simply from the symbolism displayed in the object, simply rather from the approving of the Church in the name of Jesus.[35] [36]

The crucifix, and the associated sign of the cross, is one of the key sacramentals used by Christians to ward off evil since the time of the Early on Church building Fathers; as such, many Christians clothing a cantankerous necklace.[37] [38] [39] The imperial cross of Conrad II (1024–1039) referred to the power of the cross against evil.[forty]

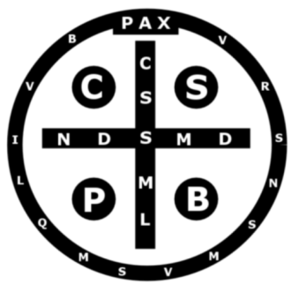

A well-known amulet associated with Benedictine spirituality present in Christianity of the Catholic, Lutheran and Anglican traditions is the Saint Bridegroom medal which includes the Vade Retro Satana formula to ward off Satan. This medal has been in utilize at least since the 1700s, and in 1742 it received the blessing of Pope Bridegroom 14. It later became part of the Roman Ritual.[41]

Several Christian saints have written about the power of holy water equally a force that repels evil; as such in Christianity (especially in the Catholic, Orthodox, Lutheran, and Anglican denominations), holy h2o is used in the dominical sacrament of baptism, equally well every bit for devotional use in the habitation.[42] [43] Saint Teresa of Avila, a Medico of the Church who reported visions of Jesus and Mary, was a stiff believer in the power of holy water and wrote that she used information technology with success to repel evil and temptations.[44]

Lay Catholics are non permitted to perform solemn exorcisms, but they tin can use holy water, blessed salt, and other sacramentals, such as the Saint Bridegroom medal or the crucifix, for warding off evil.[45]

Some Catholic sacramentals are believed to defend against evil, by virtue of their clan with a specific saint or archangel. The scapular of St. Michael the Archangel is a Roman Catholic devotional scapular associated with Archangel Michael, the chief enemy of Satan. Pope Pius 9 gave this scapular his approval, but it was first formally approved under Pope Leo 13. The form of this scapular is somewhat distinct, in that the two segments of textile that constitute information technology take the form of a small-scale shield; one is made of bluish and the other of black cloth, and one of the bands besides is blue and the other black. Both portions of the scapular carry the well-known representation of the Archangel St. Michael slaying the dragon and the inscription " Quis ut Deus? " significant "Who is like God?".[46]

Since the 19th century, devout Castilian soldiers, especially Carlist units, have worn a patch with an epitome of the Sacred Centre of Jesus and the inscription detente bala ("end, bullet").[47]

Early Egyptian Christians made textual amulets with scriptural incipits, especially the opening words of the Gospels, the Lord's Prayer and Psalm 91. These amulets have survived from late antiquity (c. 300–700 C.East.), by and large from Egypt. They were written in Greek and Coptic on strips of papyrus, parchment and other materials in gild to cure bodily illnesses and/or to protect individuals from demons.[48]

Some believers, especially those of the Greek Orthodox tradition, wear the filakto, an Eastern Christian sacramental that is pinned to 1's article of clothing to ward off Satan.[49] [50]

Almost Eastern Islamic amulets [edit]

| Identify | Wear amulets | Believe evil eye exists | Have objects against the evil eye |

|---|---|---|---|

| SE Europe | 24% | 47% | 35% |

| Cardinal Asia | xx% | 49% | 41% |

| Southeast Asia | three% | 29% | four% |

| Southern asia | 26% | 53% | 40% |

| Eye East/North Africa | 25% | 65% | 18% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | no data | 36% | no data |

Amulet containing the names of the Seven Sleepers and their dog Qitmir, 1600s-1800s.

Berber hamsa or "Manus of Fatima" amulet in silver, Morocco, early 20th century.

In that location is a long cultural tradition of using amulets in Islam,[52] and in many Muslim-majority countries, tens of percent of the population employ them.[51] Some hadith condemn the wearing of talismans,[51] and some Muslims (notably Salafis) believe that amulets and talismans are forbidden in Islam, and using them is an act of shirk (idolatry).[ commendation needed ] Other hadith back up the use of talismans with some Muslim denominations considering it 'permissible magic', normally under some weather (for instance, that the wearer believes that the talisman but helps through God'south volition).[53] [54] [55] Many Muslims practise not consider items used against the evil centre to be talismans; these are often kept in the home rather than worn.[51] Examples of worn amulets are necklaces, rings, bracelets, coins, armbands and talismanic shirts. In the Islamic context they tin also be referred to as hafiz or protector or himala significant pendant.[55]

Amulet is interchangeable with the term talisman. An amulet is an object that is generally worn for protection and almost frequently fabricated from a durable material such as metal or a hard-stone. Amulet can too be applied to paper examples, although talisman is oft used to describe these less robust and usually individualized forms. [56] In Muslim cultures, amulets often include texts, peculiarly prayers, texts from the Quran, hadiths (recorded oral histories of early Islam) and religious narratives, and religious names. The word "Allah" (God) is particularly popular, equally many believe that touching or seeing it wards off evil. The 90-9 names of God, and the names of the prophet Muhammad and his companions, are too used. The names of prophets and religious figures are felt to connect the wearer to the named person, protecting the wearer. The written stories of these people are too considered effective, and are sometimes illustrated with images of the religious figure or omens associated with them. Favoured figures include the prophet Solomon, Ali ibn Abi Talib and his sons Hasan and Husain, and the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus. Devotional manuals sometimes also promise that those reading them will be protected from demons and jinn. Apotropaic texts may even be incorporated into clothing.[52] Weapons might as well exist inscribed with religious texts thought to confer protective powers.[57] Scrolls with Qur'anic quotations, prophetic references and sacred symbols were mutual during war in the Ottoman Empire with Qur'anic verses such every bit 'victory is from God and conquest is near' (Qur. 6I:13) found on ta'wiz worn in gainsay.[55] Texts packaged in ta'wiz were most ofttimes pre-made when used past the public, only literate wearers could alter the poetry upon their discretion. While criticized past some denominations, sunni muslims are permitted to vesture ta'wiz every bit long as it consciously strengthens their bond with Allah and does non come from a conventionalities the ta'wiz itself cures or protects.

Astrological symbols were as well used,[52] specially in the Medieval period. These included symbols of the Zodiac, derived from Greek representations of constellations, and especially popular in the Heart East in the twelfth to the fourteenth centuries. Muslim artists also developed personifications of the planets, based on their astrological traits, and of a hypothetical invisible planet named Al Tinnin or Jauzahr. Information technology was believed that objects decorated with these astrological signs developed talismanic power to protect.[58]

Abstruse symbols are also common in Muslim amulets, such as the Seal of Solomon and the Zulfiqar (sword of the aforementioned Ali).[52] Another popular amulet often used to avert the evil gaze is the hamsa (significant five) or "Hand of Fatima". The symbol is pre-Islamic, known from Punic times.[59]

In Key and West Asia, amulets (often in the form of triangular packages containing a sacred verse) were traditionally fastened to the clothing of babies and young children to give them protection from forces such every bit the evil centre.[sixty] [ unreliable source? ] [61] [ unreliable source? ] Triangular amulet motifs were oftentimes also woven into oriental carpets such every bit kilims. The rug adept Jon Thompson explains that such an amulet woven into a rug is non a theme: it actually is an amulet, conferring protection by its presence. In his words, "the device in the rug has a materiality, it generates a field of force able to interact with other unseen forces and is not but an intellectual brainchild."[62] [ unreliable source? ]

Materiality of Islamic amulets [edit]

In the Islamic earth, material composition and graphic content are of import in determining the apotropaic forces of the amulets. The preferred materials employed by amulets are precious and semi-precious materials, because the inherent protective values of these materials depend hugely upon their natural rarity, monetary value, and symbolic implications.[64] Among the semi-precious materials, carnelian ('aqiq) is often favoured because it was considered as the stone of the Prophet Muhammad, who was said to take worn a carnelian seal set in silver on the little finger of his right hand.[65] [66] As well, materials such as jade and jasper are regarded as to possess protective and medicinal properties, including assuring victory in battles, protection from lightening and treating diseases of the internal organs.[67] [68] Sometimes, amulets combine different materials to achieve multiple protective effects. A combination of jade and carnelian, for instance, connotates fertility and embryogenesis. The reddish, transcalent quality of the cornelian resembles claret, which echoes the clot of congealed blood from which Allah created human (Qur. 96:2). Additionally, recurring apotropaic Qur'anic verses are often inscribed on the amulet, praising Allah every bit the ultimate bestower of security and power and every bit the provider of the Qur'an and the Prophet Muhammad.[69]

Diminutive Islamic amulets [edit]

Diminutive amulets made in the medieval Mediterranean Islamic globe include prayers executed with a cake impress or die (tarsh). Through folding, these miniature paper amulets are oftentimes even farther reduced in size in order to fit into a tiny wearable box or tubular pendant cases.[69] In other cases, yet, these protective objects remain fully loyal to the book format as miniature Qur'ans, protected by illuminated metal cases.[70]

In the Aga Khan Museum, Toronto, rests an example of an Egyptian block printed amulet, fabricated during the 10th or eleventh century. Here, 1 can notice the minuscule ink on newspaper script of the size of seven.2 10 v.5 cm.[seventy] Its text'south concluding line is a verse from the Qur'an that proclaims: 'So God will safeguard you from them. He is All-Hearing and All-Knowing' (Qur. 1:137). A tension is therefore created between the idea of Allah equally protector and the amulet equally a material item that encapsulates and transmits this divine free energy.[70] Amulets and talismanic objects were used by early Muslims to appeal to God in the first instance. In this respect, these early Islamic amulets differ substantially from Byzantine, Roman, early Iranian, and other pre-Islamic magic which addressed demonic forces or spirits of the expressionless. The main part of amulets was to ward off misfortune, "evil center", and the jinn. They were meant to promote health, longevity, fertility, and say-so. Despite regional variations, what unites these objects is that they are characterized past the use of item and distinctive vocabulary of writings and symbols. These can appear in a multitude of combinations. The of import elements to these amulets are the 'magic'vocabulary used and the heavy implementation of the Qur'an. The regional variations of these amulets each are unique; nonetheless, they are tied together through the Quranic inscriptions, images of the Prophet, astrological signs, and religious narratives.[71] Such text amulets were originally housed within a lead case imprinted with surat al-Ikhlas (Qur. n2: i-iv), a verse that instructs the worshipper to proclaim God's sanctity.[seventy] As seen in a diverse range of block printed amulets, the lead case should include lugs, which allowed the tiny package to exist either sewn onto clothing or suspended from the possessor's trunk. These small-scale containers were, most likely, kept sealed shut, their printed contents therefore invisible to a possessor who perhaps was not wealthy enough to purchase a non-serialised, handwritten amulet.[70]

Buddhism [edit]

Tibet [edit]

The Tibetan Buddhists have many kinds of talismanic and shamanistic amulets and ritual tools, including the dorje, the bell, and many kinds of portable amulets. The Tibetan Buddhists enclose prayers on a parchment scroll within a prayer wheel, which is so spun around, each rotation being i recitation of all of the stanzas within the prayer wheel.

Thailand [edit]

The people of Thailand, with Buddhist and animist beliefs, too have a vast pantheon of amulets, which are still popular and in mutual utilize by nearly people even in the nowadays twenty-four hour period. The conventionalities in magic is impregnated into Thai civilisation and religious beliefs and folk superstitions, and this is reflected in the fact that we can still see commonplace utilise of amulets and magical rituals in everyday life. Some of the more than commonly known amulets are of course the Buddhist votive tablets, such as the Pra Somdej Buddha prototype, and guru monk coins. But Thailand has an immensely large number of magical traditions, and thousands of different types of amulet and occult charm tin be found in use, ranging from the takrut scroll spell, to the necromantic Ban Neng Chin Aathan, which uses the bones or flesh of the corpse of a 'hoeng prai' ghost (a person who died unnaturally, screaming, or in other strange premature circumstances), to reanimate the spirit of the expressionless, to dwell within the bone as a spirit, and assist the owner to attain their goals. The listing of Thai Buddhist amulets in existence is a lifetime study in its own right, and indeed, many people devote their lives to the report of them, and collection. Thai amulets are still immensely popular both with Thai folk also as with foreigners, and in recent years, a massive increase in foreign involvement has caused the subject area of Thai Buddhist amulets to become a unremarkably known topic around the earth. Amulets can fetch prices ranging from a few dollars right upward to millions of dollars for a single amulet. Due to the money that can be made with sorcery services, and with rare collector amulets of the master class, at that place is also a forgery marketplace in being, which ensures that the experts of the scene maintain a monopoly on the market. With then many fakes, experts are needed for collectors to trust for obtaining authentic amulets, and not selling them fakes.[72]

Other cultures [edit]

Amulets vary considerably according to their fourth dimension and place of origin. In many societies, religious objects serve as amulets, e.g. deriving from the ancient Celts, the clover, if it has iv leaves, symbolizes good luck (non the Irish gaelic shamrock, which symbolizes the Christian Trinity).[73]

In Bolivia, the god Ekeko furnishes a standard amulet, to whom one should offering at to the lowest degree 1 banknote or a cigarette to obtain fortune and welfare.[74]

In certain areas of Bharat, Nepal and Sri Lanka, it is traditionally believed that the jackal'south horn can grant wishes and reappear to its owner at its own accordance when lost. Some Sinhalese believe that the horn can grant the holder invulnerability in any lawsuit.[75]

The Native American movement of the Ghost Dance wore ghost shirts to protect them from bullets.

In the Philippines, amulets are chosen agimat or anting-anting. According to folklore, the near powerful anting-anting is the hiyas ng saging (directly translated every bit pearl or jewel of the assistant). The hiyas must come from a mature banana and only comes out during midnight. Before the person can fully possess this agimat, he must fight a supernatural creature chosen kapre. But so will he exist its true possessor. During Holy Week, devotees travel to Mountain Banahaw to recharge their amulets.[76] [ unreliable source? ]

Gallery [edit]

-

-

Sator Foursquare, an ancient Roman amulet in the form of a palindromic word foursquare

-

-

Ancient Roman amulet from Pompeii in the class of a phallus

-

-

-

Magical mirror with Zodiac signs

-

Nez Perce talisman, made of wolf skin, wool, mirrors, feathers, buttons and a contumely bell

-

Afro-Surinamese Winti amulet

See too [edit]

- Apotropaic magic - protective magic

- Amuse - an incantation or spell

- Charmstone

- Evil center

- Hamsa

- List of good-luck charms

- Sigil

- Talisman

- Tefillin (or phylacteries) of the Jewish organized religion

Notes [edit]

- ^ Gonzalez-Wippler 1991, p. 1.

- ^ Campo, Juan Eduardo, ed. (2009). "amulets and talismans". Encyclopedia of Islam. Encyclopedia of Globe Religions: Facts on File Library of Organized religion and Mythology. Infobase Publishing. pp. 40–i. ISBN978-i-4381-2696-eight.

- ^ a b c Teeter, E., (2011), Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt, Cambridge University Press, p170

- ^ a b c d e f grand h Brier, Bob; Hobbs, Hoyt (2009). Ancient Egypt: Everyday Life in the Country of the Nile. New York Urban center, New York: Sterling. ISBN978-1-4549-0907-1.

- ^ Teeter, E., (2011), Religion and Ritual in Ancient Arab republic of egypt, Cambridge University Press, p118

- ^ Andrews, C., (1994), Amulets of Ancient Arab republic of egypt, Academy of Texas Printing, p1.

- ^ a b Andrews, C., (1994), Amulets of Ancient Egypt, University of Texas Press, p2.

- ^ Ritner, R. K., Magic in Medicine in Redford, D. B., Oxford Encyclopedia Of Ancient Egypt, Oxford Academy Press, (2001), p 328

- ^ Teeter, Eastward., (2011), Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt, Cambridge Academy Press, p171

- ^ Ritner, R.K., Magic: An Overview in Redford, D.B., Oxford Encyclopedia Of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, 2001, p 326

- ^ a b c d Mark, Joshua (2017). "Magic in Aboriginal Egypt". Earth History Encyclopedia.

- ^ Henig, Martin (1984). Organized religion in Roman United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland. London: B.T. Batsford. ISBN978-0-7134-1220-8. [ full citation needed ]

- ^ Collingwood, Robin G.; Wright, Richard P. (1991). Roman Inscriptions of United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland (RIB). Vol. II, Fascicule iii. Stround: Alan Sutton. RIB 2421.56–8.

- ^ Henig 1984, p. 187.

- ^ Parker, A. (2018). "'The Bells! The Bells! Budgeted tintinnabula in Roman Britain and beyond". In Parker, A.; McKie, S (eds.). Textile Approaches to Roman Magic: Occult Objects and Supernatural Substances. Oxbow. pp. 57–68.

- ^ Martin-Kilcher, S. (2000). "Mors immatura in the Roman earth – a mirror of society and tradition". In Pearce, J.; Millet, One thousand.; Struck, M. (eds.). Burials, Society and Context in the Roman Earth. Oxbow. pp. 63–77.

- ^ Karlheinz Kessler. 2008. Das wahre Ende Babylons – Die Tradition der Aramäer, Mandäer, Juden und Manichäer. In Joachim Marzahn and Günther Schauerte (eds.). Babylon. Wahrheit: Eine Ausstellung des Vorderasiatischen Museums Staatliche Museen zu Berlin mit Unterstützung der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. München: Hirmer. Pp. 467–486, fig. 338. ISBN 978-3-7774-4295-2

- ^ Christa Müller-Kessler, Trence C. Mitchell, Marilyn I. Hockey. 2007. An Inscribed Silver Amulet from Samaria. Palestine Exploration Quarterly 139 pp. 5–19.

- ^ Joseph Naveh, Shaul Shaked. 1985. Amulets and Magic Bowls. Aramaic Incantattion of Belatedly Antiquity. Jerusalem: Magness Press. ISBN 965-223-531-8

- ^ Joseph Naveh, Shaul Shaked. 1993. Magic Spells and Formulae. Aramaic Incantattion of Tardily Artifact. Jerusalem: Magness Press. Pp. 43–109, pls. 1–xviii. ISBN 965-223-841-4

- ^ Roy Kotansky, Joseph Naveh, and Shaul Shaked. 1992. A Greek-Aramaic silver amulet from Egypt in the Ashmolean Museum. Le Muséon 105, pp. 5–25.

- ^ Roy Kotansky. 1994. Greek Magical Amulets. The Inscribed Gilt, Silver, Copper, and Bronze Lamellae. Part I. Published Texts of Known Provenance. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.ISBN 3-531-09936-1

- ^ Wen, Benenell (2016). The Tao of Craft: Fu Talismans and Casting Sigils in the Eastern Esoteric Tradition. Northward Atlantic Books. ISBN978-1623170660.

- ^ "Shinsatsu, Mamorifuda". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Canaan, Tewfik (2004). "The Decipherment of Arabic Talismans". In Vicious-Smith, Emilie (ed.). Magic and Divination in Early Islam. The Formation of the Classical Islamic World. Vol. 42. Ashgate. pp. 125–49. ISBN978-0-86078-715-0.

- ^ Kosior, Wojciech. ""It Volition Not Let the Destroying [One] Enter". The Mezuzah every bit an Apotropaic Device co-ordinate to Biblical and Rabbinic Sources, "The Polish Journal of the Arts and Culture" 9 (one/2014), pp. 127-144". Shine Periodical of Arts and Culture, 9/2014, Pp. 127-144 . Retrieved 2016-07-thirty .

- ^ Kosior, Wojciech. ""The Proper noun of Yahveh is Called Upon You". Deuteronomy 28:10 and the Apotropaic Qualities of Tefillin in the Early Rabbinic Literature, "Studia Religiologica" two 48/2015, pp. 143-154". Studia Religiologica. 2 (48/2015): 143–154. Retrieved 2016-07-thirty .

- ^ Encyclopedia Judaica: Amulet.

- ^ Maimonides (1974). Sefer Mishneh Torah - HaYad Ha-Chazakah (Maimonides' Code of Jewish Police force) (in Hebrew). Vol. three. Jerusalem: Pe'er HaTorah. p. 57 [29a] (Hil. Isurei ha-bi'ah 15:30). OCLC 122758200. ; cf. Babylonian Talmud (Kiddushin 73b)

- ^ Guide to the Perplexed, i:61; Yad, Tefillin 5:4.

- ^ For example, Solomon ben Abraham Adret ("Rashba," 1235–1310, Espana) and Naḥmanides ("Ramban," 1194-1270, Spain). Ency. Jud., op. cit.

- ^ Conder, C.R. (1889). Syrian Stone-lore; or, The Monumental History of Palestine. London: Alexander P. Watt. p. 201. OCLC 751757461. , with a correction made for errata on page 455

- ^ Ency. Jud.: Katz, Naphtali ben Isaac. See as well Naphtali Cohen#Biography.

- ^ Kazlas, Laura (1 Feb 2015). "The Best Protection Against Demons and Evil Spirits". A Catholic Moment. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ Armentrout, Don S. (ane January 2000). An Episcopal Lexicon of the Church: A Convenient Reference for Episcopalians. Church Publishing, Inc. p. 541. ISBN978-0-89869-701-eight . Retrieved ix April 2014.

- ^ Lang, Bernhard (1997). Sacred Games: A History of Christian Worship. Yale University Press. p. 403. ISBN9780300172263.

If the person who needs to be healed is not nowadays, prayer may be said over a slice of fabric; consecrated through communal prayer (and perhaps the additional impact of a particularly gifted healer), the textile is believed to carry a healing power. The Foundations of Pentecostal Theology quotes the scriptural basis of the "prayer cloth": "And God wrought special miracles by the hand of Paul: so that from his body were brought unto the sick handkerchiefs or belts, and the diseases departed from them, and the evil spirits went out of them" (Acts 19:11-12).

- ^ "Why practice Lutherans brand the sign of the cross?" (PDF). Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. 2013. p. 2. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Samaan, Moses (25 August 2010). "Who wears the Cross and when?". Coptic Orthodox Diocese of Los Angeles, Southern California, and Hawaii. Retrieved eighteen Baronial 2020.

- ^ Liz James (30 April 2008). Supernaturalism in Christianity: Its Growth and Cure. Mercer University Press. ISBN9780881460940.

From the fifth century onward, the cantankerous has been widely worn as an amulet, and the novel Dracula treats information technology as a protection against vampires. Many Christians proceed to hang polished miniatures of the cross effectually their necks.

- ^ Fahlbusch, Erwin; Lochman, Jan Milič; Mbiti, John; Pelikan, Jaroslav; Vischer, Lukas, eds. (1999). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Translator and English linguistic communication editor: Bromiley, Geoffrey West. Boston: Eerdmans. p. 737. ISBN978-0-8028-2413-four.

- ^ Lea, Henry Charles (1896). "Chapter 12: Indulged Objects". A History of Auricular Confession and Indulgences in the Latin Church. Vol. 3: Indulgences. Philadelphia: Lea Brothers & Co. p. 520. OCLC 162534206.

- ^ Bertacchini, E. (1 January 2014). A New Perspective on the Production and Development of Cultures. Content Publishers. p. 183. ISBN9781490272306.

A holy h2o font is a vessel containing holy water generally placed most the entrance of a church building. It is used in Roman Catholic and Lutheran churches, likewise as some Anglican churches to make the sign of the cross using the holy water upon entrance and get out.

- ^ Getz, Keith (February 2013). "Where is the Baptismal Font?" (PDF). Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

By having the font at the archway of the church, and using the font every Dominicus, nosotros are intentionally and dramatically revealing the importance of Holy Baptism and highlighting it as foundational to our life in Christ. It symbolically reminds u.s. that we enter into the life of the church, into the life of Christ's body, through the birthing waters of the baptismal font, where we are built-in again from to a higher place. Dipping our fingers in the holy water of the font and making the sign of the cross, reinforces who and whose we are. We are reminded that nosotros have been baptized; daily nosotros die to sin and rise to new life in the Spirit. The font is also positioned then that from the font at that place is a direct and central path leading to the chantry, highlighting how these two Holy Sacraments are intimately connected. As we go out the church, we see the baptismal font, reminding united states of america that nosotros take been baptized, named and claimed, to serve others in proclamation and service to others.

- ^ Teresa of Ávila (2007). "Chapter 21: Holy Water". The Book of My Life. Translated by Starr, Mirabai. Boston: Shambhala Publications. pp. 238–41. ISBN978-0-8348-2303-7.

- ^ Scott, Rosemarie (2006). "Meditation 26: The Weapons of Our Warfare". Clean of Heart. p. 63. ISBN978-0-9772234-five-9.

- ^ Ball, Ann (2003). Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices. Our Sunday Visitor. p. 520. ISBN978-0-87973-910-2.

- ^ "El Regimiento "Príncipe" n.º 3 se presenta a su Patrona". ejercito.defensa.gob.es (in Spanish). Regimiento de Infantería 'Principe' nº 3. 24 Oct 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Sanzo, Joseph E. (half-dozen January 2018). "Aboriginal Amulets with Incipits Early Christian amulets". biblicalarchaeology,org . Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ Franklin, Rosalind (2005). Babe Lore: Superstitions & Old Wives Tales from the World Over Related to Pregnancy, Birth & Babycare. Diggory Press. p. 160. ISBN978-0-9515655-iv-4.

- ^ Papastergiadis, Nikos (1998). Dialogues in the Diasporas: Essays and Conversations on Cultural Identity. Rivers Oram Printing. p. 223. ISBN978-1-85489-094-viii.

- ^ a b c d "Affiliate four: Other Beliefs and Practices". Pew Inquiry Center'southward Organized religion & Public Life Project. 2012-08-09. Archived from the original on 2018-08-xi. Retrieved 2018-08-11 .

Islamic tradition also holds that Muslims should rely on God alone to keep them safety from sorcery and malicious spirits rather than resorting to talismans, which are charms or amulets bearing symbols or precious stones believed to have magical powers, or other means of protection. Perhaps reflecting the influence of this Islamic teaching, a large bulk of Muslims in near countries say they do not possess talismans or other protective objects. The utilise of talismans is most widespread in Pakistan (41%) and Albania (39%), while in other countries fewer than 3-in-x Muslims say they wear talismans or precious stones for protection. Although using objects specifically to ward off the evil eye is somewhat more common, only in Republic of azerbaijan (74%) and Kazakhstan (54%) do more than than half the Muslims surveyed say they rely on objects for this purpose. ...Although the survey finds that near Muslims practise non habiliment talismans, a substantial number of Muslims appear to make an exception for charms kept at home to ward off the evil centre

- ^ a b c d Al-Saleh, Yasmine (November 2010). "Amulets and Talismans from the Islamic World". www.metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Mufti Muhammad Taqi Usmani (May 1, 2010). "On the Permissibility of Writing Ta'widhat".

- ^ "is wearing a taweez shirk or not ? | Islam.com - The Islamic community news, discussion, and Question & Answer forum". qa.islam.com.

- ^ a b c Leoni, Francesca, 1974- (2016). Power and protection : Islamic art and the supernatural. Lory, Pierre,, Gruber, Christiane, 1956-, Yahya, Farouk,, Porter, Venetia,, Ashmolean Museum. Oxford. ISBN978-one-910807-09-5. OCLC 944474907.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Porter, Said, Cruel-Smith, Venetia, Liana, Emilie. Medieval Islamic Amulets, Talismans, and Magic.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Islamic Artillery and Armor". www.metmuseum.org. Department of Artillery and Armour.

- ^ Sardar, Marika (August 2011). "Astronomy and Astrology in the Medieval Islamic Earth". world wide web.metmuseum.org.

- ^ Achrati, Ahmed (2003). "Manus and Pes Symbolism: From Rock Art to the Qur'an" (PDF). Arabica. 50 (4): 463–500 (see p. 477). doi:x.1163/157005803322616911. Archived from the original (PDF) on xv November 2017.

- ^ Erbek, Güran (1998). Kilim Catalogue No. 1. May Selçuk A. S. Edition=1st. pp. iv–30.

- ^ "Kilim Motifs". Kilim.com. Retrieved 28 Jan 2016.

- ^ Thompson, Jon (1988). Carpets from the Tents, Cottages and Workshops of Asia. Barrie & Jenkins. p. 156. ISBN0-7126-2501-i.

- ^ rockandmineralplanet.com

- ^ Leoni, Francesca (2016). Power and Protection: Islamic Art and the Supernatural. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum. p. 35. ISBN978-1910807095.

- ^ Blair, S. (2001). An Amulet from Afsharid Iran. The Journal of the Walters Art Museum 59, pp.85–102, and Vesel (2012) p.265.

- ^ Vesel, Živa, 'Talismans from the Iranian Earth: A Millenary Tradition', in ed., Pedram Khosronejad, The Art and Material Culture of Iranian Shi'ism: Iconography and Religious Devotion in Shi'i Islam (London and New York, 2012) pp.254–75.

- ^ Keene, Thou. (n.d.). JADE i. Introduction – Encyclopaedia Iranica. iranicaonline.org. Available at: https://iranicaonline.org/articles/jade-i.

- ^ Melikian-Chirvani, A.S. (1997). Precious and Semi-Precious Stones in Iranian Culture, Chapter I. Early Iranian Jade. Bulletin of the Asia Institute 11, pp.123–73.

- ^ a b Francesca, Leoni (2016). Ability and protection : Islamic art and the supernatural. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum. pp. 33–52. ISBN978-1910807095.

- ^ a b c d eastward Leoni, Francesca (2016). Ability and protection : Islamic art and the supernatural. Oxford: Oxford: Ashmolean. pp. 33–52. ISBN978-1910807095.

- ^ Porter, Said, Savage-Smith, Venetia, Liana, Emilie. Medieval Islamic Amulets, Talisman, and Magic.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Littlewood, Ajarn Spencer (2016). The Book of Thai Lanna Sorcery (PDF). Thailand: Buddha Magic Multimedia & Publications. pp. i–two.

- ^ Cleene, Marcel; Lejeune, Marie Claire (2003). Compendium of Symbolic and Ritual Plants in Europe. p. 178. ISBN978-xc-77135-04-4.

- ^ Fanthorpe, R. Lionel; Fanthorpe, Patricia (2008). Mysteries and Secrets of Voodoo, Santeria, and Obeah. Mysteries and Secrets Serial. Vol. 12. Dundurn Grouping. p. 183–4. ISBN978-1-55002-784-vi.

- ^ Tennent, Sir, James Emerson (1999) [1861]. Sketches of the Natural History of Ceylon with Narratives and Anecdotes Illustrative of the Habits and Instincts of the Mammalia, Birds, Reptiles, Fishes, Insects, Including a Monograph of the Elephant and a Clarification of the Modes of Capturing and Grooming it with Engravings from Original Drawings (reprint ed.). Asian Educational Services. p. 37. ISBN978-81-206-1246-4.

- ^ "The Agimat and Anting-Anting: Amulet and Talisman of the Philippines". amuletandtalisman.com. 2012. Archived from the original on 2016-09-24.

References [edit]

- Budge, Due east. A. Wallis (1961). Amulets and Talismans. New Hyde Park, NY: Academy Books.

- Gonzalez-Wippler, Migene (1991). Consummate Book Of Amulets & Talismans. Sourcebook Series. St. Paul, MN: Lewellyn Publications. ISBN978-0-87542-287-nine.

- Buddha Magic Buddha Magic (Thai Occult Practices, Amulets and Talismans)

- Plinius, Due south.C. (1964) [c. 77-79]. Natural History. London.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amulets. |

| | Expect up amulet in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Amulets Thailand Amulets Buddhist Due east-Books, Thai Occultism, Publications on Amulets.

- Armenian scroll-shaped amulets Armenian prayer scrolls

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amulet

Belum ada Komentar untuk "Bed Bath and Beyond Art Tpe Trnty 14 X 16"

Posting Komentar